Born in Japan and trained at the Southern California Institute Of Architecture and Cooper Union, Shigeru Ban is—I’m informed by my architecture student friend—a big name in the field. And Ban started his lecture talking about and against big, or monumental, buildings.

Traditionally architects build monuments—skyscrapers or office complexes or museums–for the rich and powerful. Architects play, in Ban’s mind, a more responsible role to the public at large. As I understood it, architects must build for everyone.

This responsibility also extends to building safety. Earthquakes don’t kill people, Ban emphasized: buildings do. Floods often don’t kill people, but the deforestation required for buildings does.

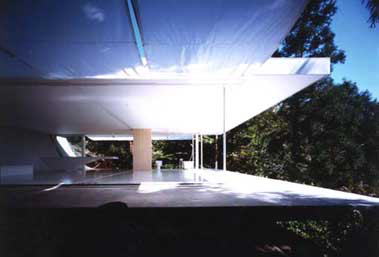

Before getting to his more famous humanitarian work, slides of Ban’s early residential work in Japan show his explorations in the confluence of interior and exterior spaces. There was a preoccupation with sliding glass doors and vertical blinds as walls. Inspired by the work of Mies Van der Rohe and traditional Japanese homes Ban found the former didn’t always need to have walls to support his ceilings while the latter’s sliding walls created more air throughput. In many cases my impression is that Ban merely builds a flat roof supported on thin columns, thus removing walls and allowing residents to freely exchange indoor/outdoor environments.

Shigerua Ban – Wall-less House – Nagano, Japan, 1997. Thin columns, sliding glass and adjustable canopy “to raise when visitors come.” Even the bathroom is out in the open.

Shigeru Ban – Shutter House for a Photographer – Tokyo, Japan, 2003. The “walls” here are adjustable blinds. Built in a crowded residential area, the horizontal slats can be rotated open and closed.

Shigeru Ban – Picture Window House – Shizuoka, Japan, 2001.

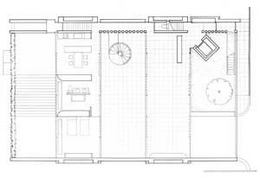

Shigeru Ban – 2/5 House – Hyogo, Japan, 1995 – The floor plan is divided into five equal rectangles three of which are outdoor.

These open designs also lend themselves to respect the way neighbours use a space before a new building arrives. In one case Ban was commissioned to build a new apartment building in a small park with existing trees. I won’t cut any trees down, Ban promised, so he built the complex around the foliage, allowing them to grow through large oval openings in the middle of the structure. Locals had also been using the park as a short cut to the bus stop so Ban left a wide breeze way open under the main area of the building.

Shigeru Ban – Hanegi Forest – Tokyo, Japan, 1997. Notice the trees through the oval openings.

Within these open designs Ban also worked with modular floor plans and their ability to configure the space as the tenant’s use changed. Nine-Square Grid House (1997) in particular is significant if just for its nomenclature: only two rooms have a label and thus explicit use: bathroom and kitchen. The remaining seven grids, by way of sliding partitions, can be whatever name and function you wish. Naked House, designed for a small family, is particularly cute. Here the only “rooms” for the kids are moveable three-sided boxes to hang out inside or on top of. If the kids want air conditioning, Ban says, they can just slide their box over to an sliding door.

Shigeru Ban – Naked House – Saitama, Japan, 2000. The kids’ rooms are on wheels.

On a larger scale Ban was given the challenge to create an portable exhibit space for a famous Canadian photographer. Rather than building an expensive and wasteful structure to bring to locations around the world Ban brought the exhibit to the structure, so to speak. Large shipping containers come, it turns out, in a world-wide standard size. By using these empty containers at each major locale the walls of the exhibit were stacked Lego-like in open-spaced grids capped by basically a plastic tarp. The design was especially modular in that it could be configured easily for varying spaces and weights (for example on old wooden docks). The best part is that material costs are almost void: crates were borrowed at each port.

Again and again Ban casually explained the impetus for his ideas developed from this simple fact: he didn’t have the money to do go big. Which is where his most famous cardboard tube buildings originated. What material is cheap, pretty strong and readily available to anyone working in the architecture (or textile) industry? The left-over tubes from big rolls of paper.

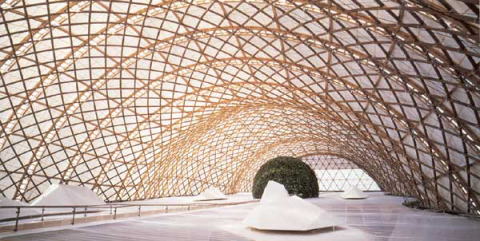

Shigeru Ban – Japan Pavillion, Expo 2000, Hannover – Germany, 2000. Paper tube construction.

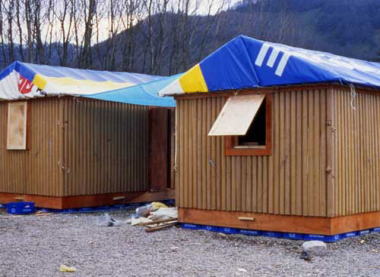

Shigeru Ban – Paper Log Houses – Kaynasli, Turkey, 2000. Quick, easy and cheap, adjustable for hot and cold climates. Even the plastic beer crate foundations are donated and chosen to match the colour of the plastic tarp roof.

In short the paper tubes are most often used as vertical supports and are surprisingly strong. Ban has built dozens of designs from huge domed exhibitions to disaster relief shelters. There’s lots of info online about Ban’s tube structures and his humanitarian work, so I’ll just summarize in a sec some of the more interesting points I came away with.

As my architecture student friend pointed out, Ban’s humble attitude and sense of humour made for a pleasant hour compared to some of the stuck-up architects he’s been lectured by. In one of his paper tube houses the toilet is actually built into a particularly large, tall and hollow column. Not only are the sound effects particularly impressive in there, mused Ban, but if you run out of toilet paper you can simply tear a new piece off the wall. On another aside, for years Ban wanted to build his own paper-tube weekend getaway but could never afford it. Now that he can (and did) he doesn’t have any weekends.

Other Shigeru Ban Points:

- Furniture both saves and kills people in an earthquake. As a sort of proof-of-concept and experiment Ban constructed a home almost entirely out of pre-fabricated furniture.

- There was emphasis on designs that anyone could assemble.

- Paper tubes were an acceptable material for African relief shelters. Being hollow they are not susceptible to termites (a major problem over there), which like to eat cellulose hidden from human view.

- Paper tubes are not only cheap, available and strong, but they look nice, which is important when refuge slums pop up in middle class neighbourhoods.

- Ban tries to work with a minority group (for example, a subset of refuges) because of the more manageable smaller scale, and, I’m guessing, the reward of working within a close-knit group.

- Despite frowning upon monumental architecture Ban admits he likes to make nice big buildings, too. For example, his large, paper tube relief church in Japan. But although the church still stands and everyone in the church admires it, the building was recently disassembled and loaned to a town in China destroyed by a natural disaster.

All images taken from www.shigerubanarchitects.com except the portrait (from here) and the ticket, which is mine and I scanned it.

Leave a Reply